The new gTLD program is set to launch in Q2 2026. Similar to Round One, we can expect tech entrepreneurs and industry domain name bodies to introduce a wide range of new domain name spaces. While these new spaces offer innovation and opportunity, they also create challenges for cybersecurity experts and brands, who must monitor and defend against a surge in phishing attacks. In this blog, we explore the upcoming new gTLD program with a focus on retail gTLDs, weighing the potential opportunities against the emerging threats.

A brief history of the new gTLD program

The journey of the new generic top-level domain (gTLD) program began under the auspices of the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN). In 2012, ICANN initiated a groundbreaking expansion of the domain name system, allowing for the introduction of numerous new gTLDs. This move was a significant departure from the limited selection of gTLDs like .com, .org, and .net that had dominated the digital landscape for years.

In total there were 1,930 new gtld applications recioeved, 1,241 successful applications, 646 withdrawn and several not approved or still going through the process.

ICANN’s Board of Directors approved a significant resolution on July 27, 2023, to advance the next phase of the New gTLD Program, which was initiated in Cancún, Mexico. This program aims to introduce new generic top-level domains (gTLDs) and has outlined a comprehensive roadmap detailing timelines, costs, system requirements, and more. The roadmap encompasses two years of policy implementation, followed by three years of program development, overlapping with policy work, and an additional operational year post-finalization of the Applicant Guidebook (AGB), expected by May 2025. This sets a tentative timeline for the next application round to begin by the second quarter of 2026. The ICANN Board emphasizes that the plan’s success hinges on continuous commitment, resources, and effort from everyone involved, warning that any delays in policy implementation could push back the start of the new round.

Distinguishing branded vs. retail new gTLDs

rThe introduction of new gTLDs has led to the proliferation of both branded and retail new gTLDs. Branded TLDs offer businesses the ability to establish their own distinct online domain space, separate from the crowded .com or .com.au namespaces. These domains are closed ecosystems controlled by the brand itself, allowing for greater oversight and control of domain usage. Companies can create a clear, identifiable online presence, ensuring their brand remains front and center.

In contrast, retail gTLDs are open for public registration, which significantly increases the potential for misuse. These gTLDs are often exploited by malicious actors for phishing attacks, counterfeit sites, and other fraudulent activities. The open nature of retail new gTLDs makes it difficult for companies to defend their brands against misuse, as anyone can register domain names that mimic brand-related terms or keywords. This blog focuses specifically on retail new gTLDs.

Was the previous new gTLD program a success?

The New gTLD program has garnered a diverse array of opinions from champions, critics, interest groups, and experts, who have extensively debated its overall merits. There is a rich selection of opinions (including this one), reviews, and blogs on this matter making it a subject of interesting discussion. While the question of its success may seem straightforward, the answer is complex, given the multitude of perspectives that must be considered.

If success were measured purely by numbers, the creation of 130 million new domain names would undoubtedly mark the program as a resounding triumph. It’s argued that these new domain name spaces have expanded options for consumers by breaking down the constraints of the old TLD model. This expansion has been particularly beneficial for companies struggling to find available domain names in the highly saturated traditional TLD spaces. Suddenly, these businesses could select domain names incorporating their brand, coupled with relevant TLDs that directly reflect their industry or business type.

While the program has certainly broadened choices and opened up new opportunities for businesses to establish a distinctive presence in domain spaces beyond the ubiquitous .com, it has also introduced significant challenges. Cyber-security specialists, lawyers, and brand protection agencies, in particular, have found themselves faced with an increased workload (and headaches), navigating the complexities that come with the expanded domain name landscape.

Are retail new gTLDs actually being used?

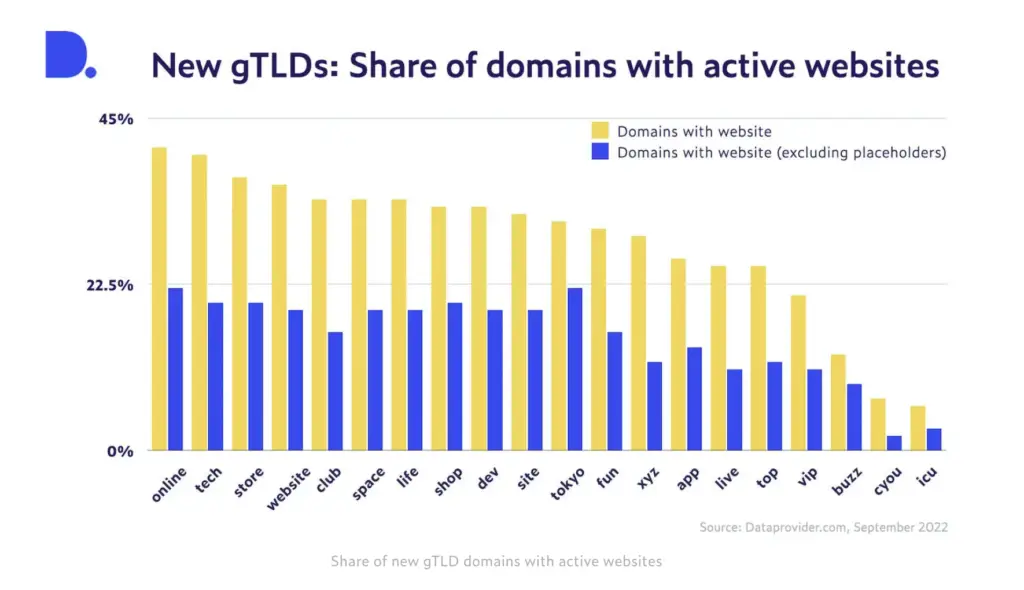

Veronika Vilgis, in her article ‘Beyond registration numbers: how popular are new generic TLDs?’ over a year ago, delved into the actual usage and popularity of new gTLDs. Analysis revealed that .xyz, .online, and .top had the highest registrations, but associations with active websites were more telling. Among the largest new gTLDs, .online, .tech, and .store – 41%, 40%, and 37% of domains directed to active websites, respectively. However, when further scrutinized and the study excluded placeholders and parked domains, these numbers almost halved. In contrast, gTLDs like .buzz, .icu, and .cyou (this is important because .cyou is now the leading new gtld in total registrations) had less than 13% active webpages, with .cyou at the bottom with only 2%. Additionally, traffic analysis using a proprietary Traffic Index shows .dev, .club, and .tech as most frequently visited, indicating that high registration doesn’t always equate to active use or high traffic, a key factor in assessing the impact and success of these new gTLDs.

These findings suggest that a significant number of sites under new generic top-level domains (gTLDs) might not have much activity or content. Key points from the article include:

– High Registration but Low Active Use: While new gTLDs like .xyz, .online, and .top have high registration numbers, this doesn’t necessarily translate to a high number of active websites, implying that many domains are registered but not used for active, content-rich websites.

– Presence of Placeholders and Parked Domains: The considerable change in active website percentage, when excluding placeholders and parked domains, highlights that a substantial portion of these domains are not being used for substantive content or functional websites.

– Limited Traffic on Many Sites: The Traffic Index analysis reveals that gTLDs like .dev, .club, and .tech attract more frequent visits, while others like .icu and .buzz have a low share of domains with moderate to high traffic. This suggests that many sites within these new gTLDs are not attracting significant visitor numbers.

It can be argued that many of the new domain name created were never meant for actual use, and were designed to fill the coffeer of Registries and Registrar for defensive purposed. In 2014 several academics submitted a paper “XXXtortion?: inferring registration intent in the .XXX TLD” to the international wide world web committed conference and found that only 3.8% of xxx domains host or redirect to potentially legitimate Web content, with the rest generally serving either defensive or speculative purposes.

Defensive registrations: the .xxx case study

The ICM Registry runs the .XXX domain names, but is also the Registry behind .sex, .porn and .adult. According to ICM’s ICANN Wiki, much criticism has been leveled against ICM, starting during their application process and going forward, was the necessary defensive registration for many brand owners. ICM did make a block list for celebrities and certain other entities. It was reported that many universities were buying .xxx domains related to their schools, to avoid someone taking advantage of the name of their school, their sports teams, or their mascots and associating it with sexual material. CEO Stuart Lawley stated in an interview that ICM does not encourage defensive registration of .xxx domains. However, as of December, 2011, of the 95,000 names in root zone ending in .xxx, 84,000 were defensive registrations.

One must question the utility of a system where the majority of activity is driven by fear and protectionism rather than genuine use or innovation. When educational institutions and other entities feel compelled to purchase domains merely to prevent their misuse, it suggests a model that profits more from the anxiety of brand owners than from serving a community’s needs or fostering a healthy digital environment. This defensive rush not only incurs significant costs for these organizations but also detracts from the intended purpose of domain name expansion – to enhance choice and innovation on the internet.

The critical perspective here is that if the primary outcome of new gTLDs is to force brands and institutions into a defensive posture, funneling money into registries to avert potential harm rather than to realize potential benefits, then the program’s success is questionable. It appears to be a system that capitalizes on the fear of reputational damage rather than contributing positively to the online ecosystem. This scenario warrants a reevaluation of the gTLD program’s objectives and strategies, ensuring that future expansions genuinely serve the broader interests of the internet community.

Concerns among cyber security, IP experts and brand owners

The New gTLD Programme has inadvertently escalated security risks, particularly through typosquatting, where cybercriminals exploit the vast array of new domain options to deceive consumers. In this scheme, attackers register domains closely mimicking well-known websites, but with slight variations or typos, often utilising new gTLDs. This practice preys on user errors when entering website addresses, leading them to fraudulent sites that can steal personal information or distribute malware. While specific statistics on typosquatting’s prevalence in each new gTLD vary, it’s evident that domains such as .app, .online, and .site are frequently exploited due to their generic nature and broad appeal. These gTLDs, perceived as credible alternatives to traditional domains like .com or .org, provide fertile ground for scammers to establish convincing, deceptive websites. This rising trend underscores a significant security concern, highlighting how the expansion of the domain name space can facilitate consumer fraud and cybercrime.

Domain Tools’ reports over the past few years have confirmed an increasing exploitation of new gTLDs for typosquatting attacks, targeting well-known brands and their customers. The 2023 report analysed the top ten TLDs used in phishing, malware, and spam attacks, with new gTLDs dominating each category. .cyou, in particular, has been noted for the highest number of phishing and malware domains identified. This data indicates a trend where cybercriminals prefer new gTLDs for creating domains that mimic those of reputable brands, thereby deceiving consumers.

A 2018 academic paper titled: Cybercrime After the Sunrise: A Statistical Analysis of DNS Abuse in New gTLDs, conducted an investigation of the abuse rates observed in domains using the pre-2012 and post-2012 gTLDs.They found that the incidence rate of spam-domains in the post-2012 gTLD domains was a whole order of magnitude higher than in the pre-2012 gTLD domains.

The new gTLD programme has also faced criticism from intellectual property (IP) lawyers, brand protection experts, and brand owners. Their concerns primarily focus on the increased risk of trademark infringement. Specifically, the introduction of numerous new gTLDs is seen as creating more opportunities for the unauthorised use of trademarks. Brand owners are worried that their trademarks could be exploited in these new domains, potentially leading to brand dilution and consumer confusion.

Another major concern is the financial impact, particularly regarding defensive registrations, the extension of Trademark Clearinghouse (TMCH) applications, and further domain name blocking services. Brand owners are faced with the burden of defensively registering their trademarks across a multitude of new domains to prevent misuse. This requirement is viewed as a significant and unwelcome financial drain, especially for smaller businesses with limited resources. These challenges highlight the complexities and potential drawbacks of expanding the domain name system under the new gTLD programme.

Greater choice: The new gTLD promise vs. market reality

As discussed, the new gTLD program was initiated to expand the spectrum of domain name choices. However, the program’s aspiration to create a more inclusive digital space is being undermined by a very active secondary market. In this market, major industry players deploy advanced technologies to swiftly claim premium domain names upon their release. This rapid and strategic capture of new, sought-after domain names is dominated by a narrow segment of the market, leaving brands and consumers at a significant disadvantage. Consequently, these parties are often forced to purchase domain names, originally intended to broaden choice, at prices that can exceed the initial registration cost by more than a hundredfold.

The grip on domain names is maintained predominantly by Registrars, dedicated aftermarket websites and domain name brokers with significant resources, who employ sophisticated registration tools and strategies. It presents a considerable hurdle for individuals and smaller entities, who find themselves competing against inflated prices for desirable domain names. Thus, the core objectives of the new gTLD program — to foster diversity and ensure equitable access — are being overshadowed. The market dynamics heavily favor those with the focussed capability and technology to quickly secure these valuable new gtld assets, compromising the program’s foundational principles of inclusivity and broadened choice.

Who has benefited the most from new retail gTLDs?

The biggest winner of the new gTLD Program (in relation to the retail rollout of retail domains) has undoubtedly been the domain name industry itself, a fact that casts a somewhat cynical light over the motivations behind future TLD expansion endeavours. Hundreds of Millions of dollars have flowed into the industry’s coffers, driven by activities such as registering, renewing, investing, selling, and paradoxically, protecting against these very gTLDs. This financial windfall, however, prompts questions about the real beneficiaries of the programme.

The retail influx of new gTLDs has predominantly advantaged domain registrars and speculators, who have seized the opportunity to profit from the rush to secure and safeguard brand-related domains. This ‘gold rush’ has resulted in a defensive and often costly reaction among businesses and brand owners to prevent potential cybersquatting and trademark infringement. Moreover, the introduction of new retail gTLDs has complicated the domain name landscape, necessitating enhanced governance, policy development, and leadership. This complexity ensures that the policy makers, along with the industry they represent, will remain relevant and influential for years to come.

So do we need more retail new-gtlds?

In summary, the expansion of retail new gTLDs, originally intended to spur innovation and enhance choice, has paradoxically cultivated an environment ripe for typosquatting, undermining consumer trust and burdening brands with exorbitant protection costs. As we approach the introduction of a new set of gTLDs in early 2026, brand owners and cybersecurity experts should be wary of the added complexity and potential vulnerabilities this expansion could inject into our domain name system.

Reflecting on the pivotal question – whether we truly need more domain name spaces in our digital lives – while they represent opportunities for brands to redfine their digital identities, the evidence for retail new gTLDs suggest not. The data implies that the domain name system would benefit more from a strategic consolidation, focusing on domains that contribute real value beyond mere financial gains for the domain name industry. This approach would not only streamline the system but also prioritize its integrity and the interests of the broader online community.

As a participant in the corporate domain name management space, I advocate for a critical evaluation of the programme’s outcomes. Our role extends beyond just selling domain names; it involves being a voice for our clients, guiding them through the complexities of the digital landscape. We must weigh the benefits of new domain spaces against the risks and costs they impose on brand owners. This balanced perspective is vital in ensuring that future developments in the domain name system align with the genuine needs and interests of the broader online community, rather than being driven by financial incentives alone.

About brandsec

brandsec is an Australian domain name management provider that offers online brand management solutions to corporate and government organisations. Our services include domain name management, domain name security, domain name policy development, dispute management, monitoring, and enforcement services. Additionally, brandsec offers a comprehensive online brand protection service that covers various platforms such as websites, social media, email, and online marketplaces. The service addresses issues related to counterfeiting, fakes, copyright infringement, intellectual property (IP) matters, piracy, and other intellectual protection-related issues.

Opinion and analysis by Ed Seaford, Managing Director of brandsec

Image by benzoix on Freepik